By G J Gillespie

One contribution to the study of reason based on ancient

Greek and Roman teachers and developed in the twentieth century is the movement

metaphor. This is the belief that reasoned persuasion is best explained as

movement from diverse points on a plane to a single spot. To persuade an

audience is to move them closer to our position. We advance ideas to sway

others. Reasoning is a force we use to convince others.

One contribution to the study of reason based on ancient

Greek and Roman teachers and developed in the twentieth century is the movement

metaphor. This is the belief that reasoned persuasion is best explained as

movement from diverse points on a plane to a single spot. To persuade an

audience is to move them closer to our position. We advance ideas to sway

others. Reasoning is a force we use to convince others.

In advanced mathematics and physics, the idea of an imaginary space is called a manifold. An object in a manifold has a velocity that propels it across a plane from A to B. An arrow represents the velocity. The distance between A and B is called the order of magnitude.

We see that the geometrical concept of a manifold is very

much like an argument. An argument has a line of reasoning that is like the

arrow of velocity: A (support) - - > B (claim). Like gravity or the nuclear

force inside atoms, reasoning in an argument is the force that binds support to

the claim. Without the binding force of reasoning, the bits of supporting

material float chaotically -- appearing as random data that make no sense. When we add reasoning in the mix, the bits of

data cohere to form a pattern that makes sense. Children playbooks ask the

reader to connect dots to create a picture of a cat, horse or in this case, a goose. (Connect the Dots). Reasoning is

connecting the dots, pulling together bits of information to form a bigger picture. After hearing a persuasive argument, the audience will have an

“Ah-ha” moment. “Now I get it!”

We see that the geometrical concept of a manifold is very

much like an argument. An argument has a line of reasoning that is like the

arrow of velocity: A (support) - - > B (claim). Like gravity or the nuclear

force inside atoms, reasoning in an argument is the force that binds support to

the claim. Without the binding force of reasoning, the bits of supporting

material float chaotically -- appearing as random data that make no sense. When we add reasoning in the mix, the bits of

data cohere to form a pattern that makes sense. Children playbooks ask the

reader to connect dots to create a picture of a cat, horse or in this case, a goose. (Connect the Dots). Reasoning is

connecting the dots, pulling together bits of information to form a bigger picture. After hearing a persuasive argument, the audience will have an

“Ah-ha” moment. “Now I get it!”

Strong arguments have high magnitude – meaning that when we add up a variety of

supporting evidence it leads us to accept the claim. Just as high magnitude stars shine bright in our physical universe, so once we hear a strong argument, it dominates our thinking. Opponents find strong arguments difficult to dismiss, refute or ignore. We may look to the bright ideas of a strong argument to guide our thinking, exactly as ship captains of the past looked to the stars for navigation.

Similarly there are four fundamental forces that bind points together in argument space: reasoning by generalization, analogy, cause-effect and authority. Like physical laws, each force of reasoning also has logical laws and rhetorical principles that we can use to predict the persuasiveness of an argument based on them.

Modern rhetorician Richard Weaver lists the four types in a hierarchy from the most ethical to the least ethical.

Argument from:

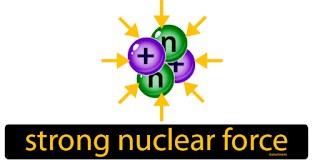

Finally we turn to the fourth fundamental force, the

strong nuclear, and compare it to

reasoning by generalization. Strong nuclear force is what holds atoms together. It binds protons and neutrons to form the nucleus of an atom. On a smaller scale, the strong force also binds the subatomic particles (quarks and gluons) that make up protons and neutrons. It is the strongest of all physical forces. When this atomic bond is broken it results in an explosion of massive energy -- utilized by nuclear power as well as weapons.

Quest for the Dark Matter of Argument

Citations

“Nothing exists except atoms and empty space; everything

else is opinion.” -- Democritus (460 -- 370 BCE)

The fact that the universe is intelligible permits

scientific discoveries. Scientists apply reasoning

to discover physical laws that govern our universe -- such as Isaac Newton’s inverse square law of gravity

(the closer you get to a point, the stronger the force). Usually truths that

advance culture are established only after a long period of debate among the

experts who fight over various proposals and hypotheses until a majority acquiesce. The ability to debate

is an essential part of what it means to be human. We question accepted ways of

doing things. We argue over ideas to shape the direction of our future. We present interpretations of what is

observed, until others offer better explanations.

The controversial theories of Newton were

vigorously challenged by his opponents at first. But, he was able

to prove his contentions by scientific experiments -- which became strong

evidence in support of the new perspectives.

Newton’s reasoning eventually led to the discoveries such as the steam

engine and electricity that made the industrial revolution possible. All social

progress follows a period of reasoned debate by advocates who are able to convince the majority to take a shared position.

More recently physicists have debated the nature of

fundamental particles, stellar objects and cosmic forces. The existence of

black holes, (Overbye) the Higgs Boson – the theorized “God particle” (Weinberg) -- and mysterious

dark matter and dark energy (Kahn) (thought to make up 95 percent of the universe)

spurred heated debate among cosmologists – until recent scientific experiments

confirmed that these properties actually do exist. Before the experimental

evidence gave weight to the theories experts were all over the map, each taking

a different stand. After the arguments were settled, most of these scientists

moved to occupy a single spot on the landscape of knowledge. It may be that

discoveries in quantum mechanics will lead to new technologies we might

currently find hard to even imagine.

In advanced mathematics and physics, the idea of an imaginary space is called a manifold. An object in a manifold has a velocity that propels it across a plane from A to B. An arrow represents the velocity. The distance between A and B is called the order of magnitude.

We see that the geometrical concept of a manifold is very

much like an argument. An argument has a line of reasoning that is like the

arrow of velocity: A (support) - - > B (claim). Like gravity or the nuclear

force inside atoms, reasoning in an argument is the force that binds support to

the claim. Without the binding force of reasoning, the bits of supporting

material float chaotically -- appearing as random data that make no sense. When we add reasoning in the mix, the bits of

data cohere to form a pattern that makes sense. Children playbooks ask the

reader to connect dots to create a picture of a cat, horse or in this case, a goose. (Connect the Dots). Reasoning is

connecting the dots, pulling together bits of information to form a bigger picture. After hearing a persuasive argument, the audience will have an

“Ah-ha” moment. “Now I get it!”

We see that the geometrical concept of a manifold is very

much like an argument. An argument has a line of reasoning that is like the

arrow of velocity: A (support) - - > B (claim). Like gravity or the nuclear

force inside atoms, reasoning in an argument is the force that binds support to

the claim. Without the binding force of reasoning, the bits of supporting

material float chaotically -- appearing as random data that make no sense. When we add reasoning in the mix, the bits of

data cohere to form a pattern that makes sense. Children playbooks ask the

reader to connect dots to create a picture of a cat, horse or in this case, a goose. (Connect the Dots). Reasoning is

connecting the dots, pulling together bits of information to form a bigger picture. After hearing a persuasive argument, the audience will have an

“Ah-ha” moment. “Now I get it!”

The principle of connection in reasoning is like the

velocity of movement of physical objects in space. Reasoning channels the

energy in the support to propel an argument forward. The amount of ground that

is covered from A to B, that is, how firm the connection between the support

and the claim is established is the magnitude of an argument.

|

| Wishing Well by GJ Gillespie |

Strong arguments have high magnitude – meaning that when we add up a variety of

supporting evidence it leads us to accept the claim. Just as high magnitude stars shine bright in our physical universe, so once we hear a strong argument, it dominates our thinking. Opponents find strong arguments difficult to dismiss, refute or ignore. We may look to the bright ideas of a strong argument to guide our thinking, exactly as ship captains of the past looked to the stars for navigation.

On the other hand, weak arguments have low magnitude, or

weak persuasive force. These are dim bulbs that fail to enlighten. The support

does not lead decisively to the claim. Just as the connections between the bits

of support along the line of reasoning in a strong argument are difficult to

break, a weak case is easy to tear apart. An opponent can point out that the

support is insufficient, flawed, or irrelevant. The reasoning in poorly

constructed arguments may be so fuzzy that the argument fails to make a clear

mental picture. The idea falls flat. The

audience is unmoved or maybe even confused.

Again, the simple model of an argument can be visualized

as the connection between two points on a two-dimensional plane: Support - -

> Claim.

We can add other more complex models of how arguments

flow. The chain model is a continuation of the simple model in which once a

claim has been proven, it functions as support for a larger claim one after

another. Each point is logically connected and builds on the point before.

Support - - > Support - - > Claim

Support - - > Support - - > Claim

The cluster model is a collection of independent reasons

that each lends support for the claim.

Support - - > Claim < - - Support

If it is true that persuasion is like momentum

Support - - > Claim < - - Support

If it is true that persuasion is like momentum

Reasoning as Force in Argument Space

Reasoning as Force in Argument Space

A force in physics is said to be the strength or energy

that causes an object to undergo a change in speed, direction, or shape. There are four fundamental forces that govern

the universe: gravity, electromagnetism, weak nuclear and strong nuclear. These forces rule how planets, moons, stars

and galaxies interact.

Similarly there are four fundamental forces that bind points together in argument space: reasoning by generalization, analogy, cause-effect and authority. Like physical laws, each force of reasoning also has logical laws and rhetorical principles that we can use to predict the persuasiveness of an argument based on them.

Modern rhetorician Richard Weaver lists the four types in a hierarchy from the most ethical to the least ethical.

Argument from:

1. genus or generalization.

2. similitude or analogy.

3. circumstance or cause and effect.

4. testimony or authority. (Weaver)

Starting with the weakest and moving

to the strongest form of reasoning, let us consider how each compares to the fundamental forces.

|

| Nocturnum by GJ Gillespie |

Gravity is like Authority

Gravity in the physical universe is a force that pulls

matter together. It shrinks the distance between objects. The

more mass of an object, the stronger the gravitational pull it exerts. The

effects of gravity also depend on proximity since attraction increases the nearer you are to a massive

object. This is known as the inverse square law: the intensity is inversely proportional to the distance from the source. Even though the sun is one

million, three hundred thousand times larger than the earth, we are held to the

ground by the earth’s gravity because we are closer to the earth.

In the argument universe, reasoning also is a force that

pulls debate matter together. The first example of the pull of reasoning

between forms of supporting matter we will consider is reasoning by authority.

These are arguments which rely on the strength of a trusted external

source.

We might say that the pull of authority in the rhetorical

universe is like gravity in the cosmos.

Ideas that are shared by credible authorities possess

persuasive weight for listeners. When an audience hears testimony from experts

or eyewitnesses, or is given the conclusions of published scientific studies,

their thinking will move closer to the position advocated. Just as the inverse square rule of physics

shows that proximity increases force, the closer an audience is to the position

of an authority, the stronger the persuasive force. If the authority is

perceived as a role model or is highly respected, an audience will find it difficult to dismiss.

Reasoning by authority draws upon collective wisdom of

philosophers or sages in producing artifacts like sacred scripture or founding

political documents such as the Constitution or Bill of Rights. The sway of cultural authorities (religious

leaders, artists, writers, sports or film stars) is especially powerful. The

findings by scientists in published studies using the scientific method may be

inescapable. Like the effects of gravitational fields spreading across the

cosmos, reasoning by authority is a pervasive force across the argument

universe. If authorities are on your

side, you will probably win the debate.

However, an advocate who simply cites an authority and is

done with it -- who fails to provide other arguments to back up a claim -- will

probably have a very weak persuasive impact. Because Weaver believed that

"an argument based on authority is as good as the authority," he

placed authority as the weakest argument type in his hierarchy. (Johannesen)

Similarly physicists say that gravity is the weakest of

the four fundamental forces. Out of the

millions of celestial objects floating in space a smaller body must be close to

a more massive object before the force of gravity is felt. In the same way,

audience members must be close to the authority who is recognized to have

persuasive weight. In other words, he or she must already be in the orbit or

pull of that authority's influence.

While we are familiar with the force of gravity in our

everyday lives, a second fundamental force is invisible to us. Yet it turns out

to be essential for our very existence.

Analogy is like Weak Nuclear Force

Analogy is like Weak Nuclear Force

Second, let’s consider how weak nuclear force is similar to

reasoning by analogy and the creation of original metaphors.

According to physicist Micahio Kaku, the weak nuclear

force is

“responsible for radioactive decay. Because the weak

force is not strong enough to hold the nucleus of the atom together, it allows

the nucleus to break up or decay. Nuclear medicine in hospitals relies heavily

on the nuclear force. The weak force also helps to heat up the center of the

Earth via radioactive materials, which drive the immense power of volcanoes.

The weak force, in turn, is based on the interactions of electrons and

neutrinos (ghost-like particles that are nearly massless and can pass through

trillions of miles of solid lead without interacting with anything). These

electrons and neutrinos interact by exchanging other particles, called W and Z

bosons.” (Kaku)

In addition to permitting subatomic particles to interact

and release energy, Kaku says the weak nuclear force causes the fusion that

fires the sun and stars. Just as the weak force causes light to shine making it

possible to see around us, an apt analogy in an argument is enlightening. While

light is actually part of the electromagnetic spectrum; it has its source in

the weak force. When the landscape is dark, travelers can look to stars in the

night skies as glimmering points of navigation. In the same way, analogies are

points in the rhetorical skies that guide our thinking – especially when an

audience is unsure.

Without the weak force human life on earth would be

impossible. Likewise since "all language is metaphorical," without

metaphor and analogy language would be impossible. When we consider how new

metaphors are generated we see more similarities between reasoning by analogy

and the weak force.

Quantum tunneling is like an analogy or metaphor in that

the persuasive energy in one body of matter “crosses over” to another unrelated

body of matter. Normally an impenetrable barrier of logic separates the two

material objects being compared since there is a literal difference. Like a

person walking through a wall, or ghostly neutrinos shooting through miles of

solid lead, original metaphors do the impossible. They spark never before heard

of insight.

The weak force is said to permit “quantum tunneling”, the strange ability for particles to jump through otherwise impenetrable barriers. Electronics applies the principle in the working of transistors for radios and diodes in television screens. According to quantum mechanics, matter exists as both a wave and particle. This is the wave-particle duality. One interpretation of quantum tunneling is that particles are able to pass through barriers in the form of waves of energy. Once crossing over, the energy on the other side is the same, but the amplitude (power) is reduced.

Reasoning by analogy permits the rhetorical energy (meaning) to jump the barrier of logic by relating the two objects figuratively. The persuasive energy now flowing in the second object follows the same recognizable pattern that exists in the first -- although the amplitude is reduced, making analogy a weak form of argument. No one is forced to accept it -- although they may be more willing to listen to our other arguments.

Reasoning by analogy permits the rhetorical energy (meaning) to jump the barrier of logic by relating the two objects figuratively. The persuasive energy now flowing in the second object follows the same recognizable pattern that exists in the first -- although the amplitude is reduced, making analogy a weak form of argument. No one is forced to accept it -- although they may be more willing to listen to our other arguments.

Some destinations are so distant from the position of the

audience that we must inspire them to follow where our line of reasoning leads.

It may take a creative analogy to make them receptive. In this way, analogy in our argumentation may

be a kind of “quantum tunneling” that transports our ideas through the thickest

mental defensive walls.

While the logical jump made by the analogy may generate a

persuasive insight for the audience, they are not bound to accept it. Analogy

lacks the binding force of a literal comparison in an example. The persuasive

power of analogy and metaphor comes from generating what Kenneth Burke calls

“perspective by incongruity”. (Burke) An apt metaphor gives new thought

patterns that surpass everyday thinking and inspires emotional support for

accepting an argument.

Consider: “My love is a red, red rose.” There is a

logical barrier between “a rose” and the “my love”. Reasoning by analogy

bridges the barrier with emotional energy. The same wave pattern in a rose is

transferred to the love, which is now understood differently by the viewer

exposed to the analogy.

The tentative nature of analogy makes it the next weakest

form of argument after relying on authority alone. It is always

possible to point out false elements in any comparison or to offer competing

analogies for opposite positions. Logic does not force an audience to follow the direction that an analogy implies. They are

free to reject it in favor of a competing analogy. Similarly, physicists say

that the weak nuclear force has a field strength that has less magnitude

compared to other fundamental forces. The weak force is said to be

unable to produce “bound states” and lacks “binding energy” necessary to force

objects together at the atomic level.

Analogies at best are ways for catching attention and framing an issue, useful for winning over the heart of an audience. Subtlety may be exactly what is needed. Just as the weak nuclear force is responsible for earthquakes by heating up the molten core of the earth, so an inspirational analogy is able to shake up thinking.

|

| Map to Gilead by GJ Gillespie |

Cause and Effect is like Electromagnetism

Third, we can compare the fundamental force of

electromagnetism to reasoning by cause and effect. The essential characteristic of causation is

the idea of movement between related materials.

Showing that something is caused by a related effect in a sequence

produces the power of the argument.

We show that when one thing is observed, it is followed

by another thing in such a way that the first caused the second. We can speak

of a"chain of causation" to explain how complex events emerge. One

thing leads to another and to another. Persuasive force is therefore generated

by showing a relationship between cause and effect. In other words, the energy

of our thinking moves from the cause to the effect to a conclusion that we are

trying to prove.

An advocate is using cause – effect reasoning when he or

she argues that because people exposed to secondhand smoke have higher rates of

lung disease, secondhand smoke causes lung disease. Thus, smoking should be

discouraged. We can see a flow of

rhetorical energy from the cause (breathing secondhand smoke) to the effect

(lung disease) leads the audience to accept our claim that smoking should be

curtailed.

This flow of mental energy is similar to the physical

force of electromagnetism. Electricity can be explained as the flow of

electrons or energy between groups of related matter. We know that every atom has an electron

cloud. The electrons sometimes break free and move to other atoms meaning that

electricity is basically the movement of energy. Inventor Thomas Edison defined

it as "a mode of motion" between charged particles.

The force of cause and effect can in the same way

“charge” the matter of our arguments, filling them with persuasive energy. Just

as electricity is the movement of particles that possess either negative or

positive charges, so in a debate our points will be positive or negative –

positive matter seeks to attract the thinking of the audience to your position,

while negative matter seeks to repel them from the position of your

opponent. Likewise, the atoms in the

matter of magnetized objects are lined up, creating a magnetic field that can

attract or repel.

While other forms of reasoning besides cause and effect

can also be used to create positive and negatively charged matter in a debate,

when a debater wins causation arguments, he or she can be assured that the

thinking of the adjudicators will be lined up with their own. Causation in this

sense is a persuasive force that binds your arguments together to make them

receptive to the minds of the audience.

Usually we speak of causal relationships as increases in

probabilities rather than absolute links. Rarely do we know for certain that

one event is caused directly by another. Instead, a debater is on firmer ground

to say that the there is an increased probability of the relationship holding

true. Smoking increases the probability of cancer. We say that rhetoric (or

persuasion) is concerned with probabilities and logic is concern with

certainty.

A type of logic called a syllogism can prove the

certainty of a conclusion. If the premises are true, we can be certain of the

conclusion. All men are mortal. Socrates was a man. Therefore, Socrates was

mortal. If the premises (all men are mortal and Socrates was a man) are true,

we are certain of the conclusion (Socrates was mortal). Again, the energy of

the premises flow to the conclusion.

However, most controversies that are debated are unlike

classical syllogisms. Most of the time we can only get the audience to agree

that more than likely, or probably, we are giving them the best explanation or

plan of action. We can not be certain, but we arrive at a level of probability

good enough to take action.

The probabilistic nature of cause and effect reasoning is

analogous to physics, since quantum mechanics – the study of how energy works

on the subatomic level – is governed by what is called the “uncertainty

principle”. The uncertainty principle says that we can never be certain of the

position of an electron. Physicists can make a good guess where the electrons

will most likely be present, but they cannot say exactly. Physicists have a choice: either they can

measure where an electron is or how fast it is, but not both at the same time.

We are inherently uncertain about the quantum realm of the subatomic world. In

the same way, when it comes to predicting the future or measuring the

relationship between what causes effects to occur, we are never certain. The

best we can get when debating social policy is statistical probability. Again

we find a parallel between the forces of reasoning and the forces of nature –

which makes sense since our minds are part of nature.

Generalization is like Strong Nuclear Force

Finally we turn to the fourth fundamental force, the

strong nuclear, and compare it toreasoning by generalization. Strong nuclear force is what holds atoms together. It binds protons and neutrons to form the nucleus of an atom. On a smaller scale, the strong force also binds the subatomic particles (quarks and gluons) that make up protons and neutrons. It is the strongest of all physical forces. When this atomic bond is broken it results in an explosion of massive energy -- utilized by nuclear power as well as weapons.

In terms of argument space, just as the strong force

holds matter together in the physical universe, so generalization holds our

arguments together. And according to Weaver, generalization -- or argument by

what he calls genus -- is the strongest argument type.

There are two ways an advocate might reason by

generalization: setting down key terms or philosophical principles, and by

giving examples of a general class. By

referring to general principles or values favored by an audience, the advocate

draws them to accept a specific case.

For example: a speaker might appeal to such values as "All men are

created equal," or "Democratic forms of government are

best". Then he or she might say: We know that slavery is wrong

because all men are created equal. Or: We oppose dictatorships because

democratic systems are ideal.

Pointing out that a case supported by universal moral

principles is a form of deductive reasoning. The debater draws conclusions

based on larger premises already accepted by the audience. Once the

premise is accepted, the conclusion follows. Poet Ralph Waldo Emerson once

said: "Now that is the wisdom of a man, in every instance of his labor, to

hitch his wagon to a star, and see his chore done by the gods themselves."

Debaters will likewise hitch their wagon to the star of great moral principles

and let the force of those truths win the day. (Emerson)

Besides looking to lasting principles, the second way

that a speaker makes a generalization is by citing typical examples that

illustrate the general idea. Generalization by example works like this: say I

have a sack of apples hidden from my view. If I reach into the sack and

randomly select an apple to examine it and discover that the apple is rotten, I

will generalize that all of the apples in the sack are rotten. Examples that

illustrate a larger group are powerful.

The most effective speakers know that vivid examples and

dramatic stories are at the heart of argument. Until it is clear to an audience

that people are affected by some larger harm, it will be difficult to persuade

them to accept a solution. For example, why should we curtail video games?

Because it hurts the psychological development of children. While this point

could be supported with a statistic or scientific study, examples of harmed

children will add emotional weight to the argument. To make the point

memorable, a speaker could tell the story of specific children harmed by video

games. In this way stories embody a thesis.

In addition to individual examples to support a larger

point, we can look to the structure of a story or drama to organize our

analysis. Narrative structure follows a theme. A theme is a generally

recognized course of action among humans that is similar to what happens in a

drama or play. Themes form the basis for literary novels and films.

Usually a dramatic theme follows this pattern: A victim

is being hurt. Good guys are trying to save the victim, but they must overcome

the action of the bad guys. Besides good versus evil, another theme might be

social progression – that society is gradually improving over time as old forms

of thinking are worn out and new ideas take hold. Dramatic themes like these

glue together all the supporting material forming an overarching narrative that

makes sense of the data for the audience, binding together all of the

particular elements of our persuasive matter – just as the strong nuclear force

binds the subatomic particles of physical matter.

Communication scholar Walter Fisher proposed the

narrative paradigm of argument, claiming that all meaningful communication is a

form of storytelling. He contends that "since human beings comprehend life

as a series of ongoing narratives, each with their own conflicts, characters,

beginnings, middles, and ends, arguments will also follow a narrative pattern.

An argument is essentially a story." (Fisher)

Quest for the Dark Matter of Argument

Overall, the four types of reasoning compose the universe

of ideas just as fundamental forces shape time, space, planets, and stars. Still, mastering the techniques of argument

making may never be enough to automatically pull an audience into our sphere.

Persuasion is a mysterious art rather than a precise science. With the advent

of quantum mechanics scientists are also learning that reality is more

mysterious than once imagined.

Physicists recently have discovered that the cosmos

contains more mass than is accounted for by visible matter that we see around

us. Most cosmologists have come to believe that visible matter is only about 5

percent and that 95 percent of the mass of the universe is made of “dark matter

and dark energy.” Dark matter may be

based on a new kind of physics we have never experienced.

We could apply the concept of dark matter to public debate

when we realize that what is said -- the matter that is exchanged in the

communication between speakers and listeners -- is only a small part of the

force that influences how an audience comes to believe. Most of the pull on our

thinking is from unconscious information and cultural values that an audience

brings to the setting. A speaker trying to influence an audience will take into

account the weight of the “dark matter” of unconscious presuppositions and

cultural values by lining up his or her arguments with the unstated assumptions

hovering in the room. Harnessing this dark matter may require setting aside

analytical reasoning in favor of intuition, creativity and poetry.

In summary we see that expanding the movement metaphor to

include a comparison between physical forces and types of reasoning gives

insight into how persuasion works. Just as the discovery of the four

fundamental forces led to practical technologies like the steam engine, the

electric light, transistors, and x ray photography applying these analogies

from physics to rhetoric will aide our persuasiveness.

•Like

falling into a gravitational field of a celestial body, taking the side of

authorities near to the heart of the audience will make arguments difficult to

resist.

•Like

quantum tunneling, apt analogies, creative metaphors and comparisons have the

surprising ability to break through walls of resistance, permitting an audience

to see the light of our perspective.

•Like

a jolt of electricity, revealing the chain of cause and effect that make up a

controversy will charge our case with power.

•And,

like nuclear forces inside atoms, tying our case to universal principles --

justice, equality or freedom -- and by storytelling -- we will strengthen the

binding force of ideas.

With the continued promise of new discoveries, there are

countless more comparisons between physics and the human mind. As nuclear

physicist Isidor Rabi predicted:

“I don’t think that physics will ever have an end. I

think that the novelty of nature is such that it’s variety will be infinite –

not just in changing forms but in the profundity of insight and the newness of

ideas.” (Rabi)

Democritus, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (date

accessed: July 23, 2012, < http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/democritus/

> )

Overbye, Dennis, "Astronomers Discover Biggest Black Holes Yet", New York Times, December 5, 2011. (Date accessed: July 26, 2012, < http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/06/science/space/astronomers-find-biggest-black-holes-yet.html >)

Weinberg, Steven, "Why the Higgs Boson Matters", New York Times, July 13, 2012. (Date accessed July 26, 2012. < http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/14/opinion/weinberg-why-the-higgs-boson-matters.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all >)

Kahn, Amina, "Dark Matter Filament Found, Scientists Say, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2012. (Date accessed: July 24, 2012. < http://articles.latimes.com/2012/jul/04/science/la-sci-dark-matter-filament-20120705 > )

Overbye, Dennis, "Astronomers Discover Biggest Black Holes Yet", New York Times, December 5, 2011. (Date accessed: July 26, 2012, < http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/06/science/space/astronomers-find-biggest-black-holes-yet.html >)

Weinberg, Steven, "Why the Higgs Boson Matters", New York Times, July 13, 2012. (Date accessed July 26, 2012. < http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/14/opinion/weinberg-why-the-higgs-boson-matters.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all >)

Kahn, Amina, "Dark Matter Filament Found, Scientists Say, Los Angeles Times, July 4, 2012. (Date accessed: July 24, 2012. < http://articles.latimes.com/2012/jul/04/science/la-sci-dark-matter-filament-20120705 > )

Connect the Dots: Free Printable Pages, www.Coloring.ws. Date accessed: 7 26, 2012. < http://www.coloring.ws/t_template.asp?t=http://www.coloring.ws/ctd/cdgoose.gif

>

Weaver, Richard, The Ethics of Rhetoric. Chicago: Henry

Regnery Company, 1953. 56.

Johannesen, Richard L., Rennard Strickland, & Ralph

T. Eubanks, Eds. Language Is Sermonic: Richard M. Weaver on the Nature of

Rhetoric. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1970. 216.

Kaku, Michio, Parallel Worlds, A Journey Through

Creation, Higher Dimensions, and the Future of the Cosmos, Anchor Books, A

Division of Random House, Inc, New York, 2005. 80.

Burke, Kenneth,

Permanence and Change: An Anatomy of Purpose, Los Altos, CA: Hermes

Publications, 1954.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo, The Atlantic Monthly; April 1862;

American Civilization - 1862.04; Volume IX, No. 54. 502-511

Fisher, Walter R. Human Communication as Narration:

Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and Action. Columbia: University of South

Carolina Press, 1989.

Rabi, Isidor -- cited in Zukav, Gary, The Dancing Wu Li

Masters, Harper Collins, 1979.

345.